The Sutton Hoo Discovery: Anglo-Saxon Ship Burial

In 1939, archaeologists discovered a 1,400-year-old Anglo-Saxon burial site in Suffolk that included an entire ship.

The finds were described as some of "the greatest archaeological discoveries of all time."

The year was 1939 when a remarkable excavation uncovered the burial mounds at Sutton Hoo.

This discovery, led by archaeologist Basil Brown, revealed an astonishing array of artefacts within the mounds, shedding light on a previously enigmatic era of British history.

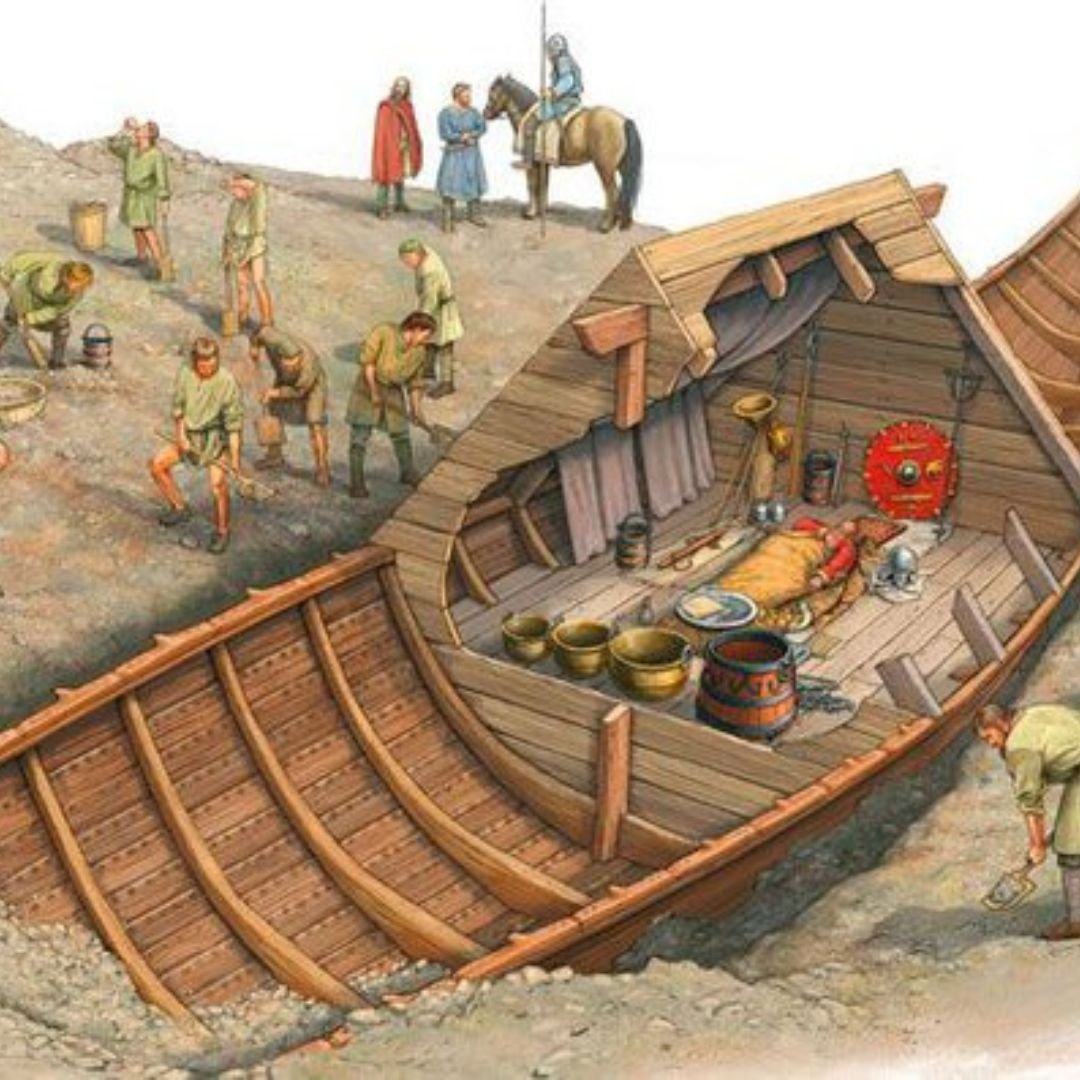

Archaeologists painstakingly brushed away layers of sandy soil to reveal the shape of a ship beneath a mound.

In the centre of a 27-meter-long wooden ship, they found a burial chamber full of the most extraordinary treasures.

It turned out to be an Anglo-Saxon royal burial of incomparable richness, and would revolutionise the understanding of early England.

The most iconic find was the burial of an Anglo-Saxon king or noble, presumed to be Raedwald, ruler of the East Angles.

He was the 7th-century king of East Anglia, and the first king of the East Angles to become a Christian.

Alongside the ship, a wealth of treasures also emerged, showcasing the exquisite craftsmanship of the time.

Among the exciting treasures found within the burial chamber was the iconic Sutton Hoo Helmet.

The helmet was a masterpiece of Anglo-Saxon craftsmanship, the intricately designed helmet stands as one of the most iconic artefacts from the site.

Adorned with depictions of warriors, animals, and scenes from Norse mythology, the helmet remains a symbol of the era's artistic and military prowess.

Highly corroded and broken into more than 100 fragments when the burial chamber collapsed, the helmet took the conservation team at the British Museum many years to reconstruct.

The Sutton Hoo sword was amongst the most significant finds.

This sword, dating to approximately AD 620, is thought to have belonged to one of four East Anglian kings: Eorpwald, Raedwald and co-regents Ecric, and Sigebert.

A study of the Sutton Hoo sword has led people to believe that the owner was left-handed, with patterns of wear indicating it was worn on the right side and carried in the left hand.

Anglo-Saxon sword blades were made using a technique known as pattern-welding, where rods of iron were twisted and then forged to form the core of a blade, to which sharp cutting edges were added.

This method gave the blade an intricately patterned appearance resembling herringbone or snake-like markings.

The sword-blade found in the Sutton Hoo ship burial is especially complex.

The sword is richly furnished with gold hilt (handle) fittings.

The pommel is inlaid with garnet cloisonné, the guards are made from gold plates, and the grip has two gold mounts decorated with delicate filigree.

Worn patches on the sword’s pommel were probably caused by the owner’s hand or clothing rubbing it when the sword was sheathed at his side.

The sword was buried in a wooden scabbard bound in leather and lined with sheep wool, whose oil kept the blade bright.

Two button-shaped mounts and two pyramid-shaped fittings, also gold with garnet inlays, were associated with the scabbard.

The sword hung from a belt whose fittings are equally magnificent. All are made of gold with inlaid garnet cloisonné.

One of these, the T-shaped strap distributor, is made of three moving parts.

On the back of one mount are the marks of a tiny goldsmith’s hammer where a repair has been made.

The artefacts of this burial were chosen to reflect the high rank of the king, and to equip him for the Afterlife.

Gold and Jewelled Items were also discovered in the burial.

A fascinating gold belt buckle found amongst the items was a masterpiece, which was exquisitely crafted from over 400 grams of gold.

It was crafted with an intricate decoration of interlocking creatures crafted in niello (black metal alloy).

Such animal ornaments were popular among many Germanic-speaking peoples at the time.

The site also contained objects that showed that people in England during Anglo-Saxon times must have traded with the rest of Europe.

The objects included a large silver dish made in Byzantium (in what is now Turkey) in about 500 ce and a set of silver bowls from the Mediterranean.

These artefacts provided invaluable insights into early Anglo-Saxon society their burial rituals, craftsmanship, trade networks, and artistic expressions.

Artefacts are now showcased in museums worldwide, captivating visitors and fostering a deeper appreciation for the cultural heritage of the Anglo-Saxons.

Additionally, ongoing research and analysis of the findings continue to contribute to scholarly discussions and debates about the era.

The effort and manpower that would have been necessary to position and bury the ship is extraordinary.

It would have involved dragging the ship uphill from the River Deben, digging a large trench, cutting trees to craft the chamber, dressing it with finery and raising the mound.

Plus, ship burials were rare in Anglo-Saxon England – probably reserved for the most important people in society – so it's likely that there was a huge funeral ceremony too.

Eighty-two years later, the Sutton Hoo ship burial is back in the public eye thanks to The Dig, a new Netflix movie starring Carey Mulligan.

The movie was a big success, and it tells the slow-burning story with understated and genuine drama throughout.

During the 1960s and 1980s, the wider area was explored by archaeologists and other individual burials were revealed.

Another burial ground is situated on a second hill-spur about 500 metres (1,600 ft) upstream of the first.

It was discovered and partially explored in 2000 during preliminary work for the construction of a new tourist visitor centre.

The tops of the mounds had been obliterated by agricultural activity.

Humans had been burying people in ships for centuries and millennia.

The same went for grave goods. In early medieval Europe, people were rarely buried without at least some of the things they held dear.

If you’d like to learn more, a number of items are on display at the British Museum.

You can also visit the Sutton Hoo site itself, as it’s currently open to visitors and run by The National Trust.

Prices start at £16 for adults, please check the National Trust website for full details and opening times.

If you enjoyed this blog post, please follow Exploring GB on Facebook for daily travel content and inspiration.

Don’t forget to check out our latest blog posts below!

Thank you for supporting Exploring GB.