The Sweet Track, Somerset: Britain’s Oldest Wooden Trackway

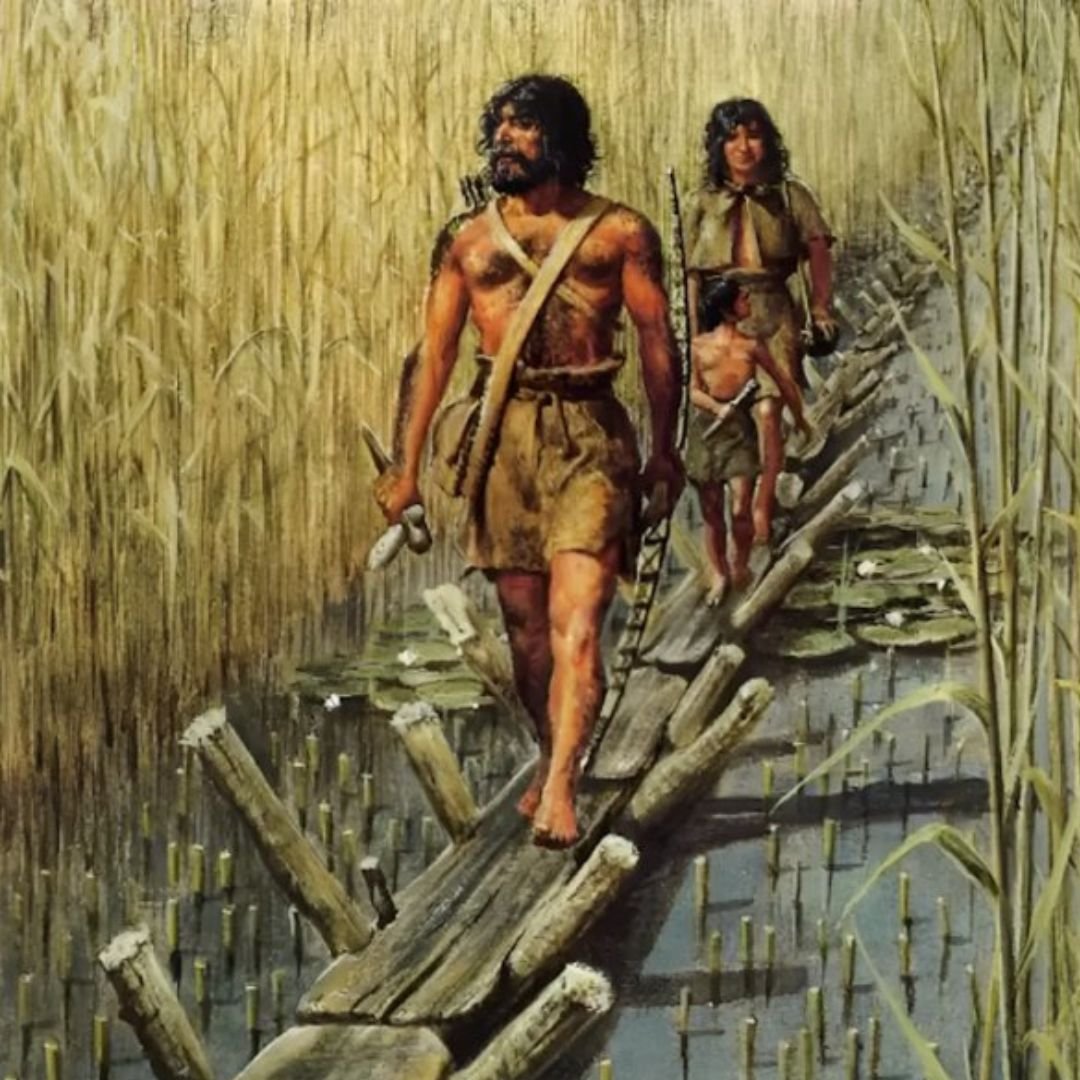

The Sweet Track is a 5,800 year old Neolithic timber walkway in Somerset, discovered in 1970.

Built to provide a dry path across the marshy ground, it's one of the world's oldest roads and Britain's oldest wooden walkway.

The Sweet Track is a very early Neolithic wooden trackway, built as a single plank raised walkway across almost 2 kilometres of reedswamp, between the Polden hills and the island of Westhay, Glastonbury.

It was constructed by the first farming communities in 3,806 BC.

Construction was of crossed wooden poles, driven into the waterlogged soil to support a walkway that consisted mainly of planks of oak, laid end-to-end.

The track was used for a period of only around ten years and was then abandoned, probably due to rising water levels.

Following its discovery in 1970, most of the track has been left in its original location, with active conservation measures taken, including a water pumping and distribution system to maintain the wood in its damp condition.

Some of the track is stored at the British Museum and at the Museum of Somerset in Taunton.

The Sweet Track is named after Ray Sweet, the peat digger who discovered it in 1973.

According to Historic England, a wide range of Neolithic material culture was deposited beside the trackway, including polished stone and flint axes, flint arrowheads, fine pottery and a range of organic objects including a wooden bowl.

The presence of high-quality burnished pottery and a polished jadeite axe from the Alps with no handle, suggest that deliberate votive deposition of objects was taking place beside the trackway.

The Sweet Track is the earliest structure in the UK associated with such ritual offerings.

Before this human incursion, the uplands surrounding the levels were heavily wooded, but local inhabitants began to clear these forests about this time to make way for an economy that was predominately pastoral with small amounts of cultivation.

During the winter, the flooded areas of the levels would have provided this fishing, hunting, foraging and farming community with abundant fish and wildfowl.

In the summer, the drier areas provided rich, open grassland for grazing cattle and sheep, reeds, wood, and timber for construction, and abundant wild animals, birds, fruit, and seeds.

The need to reach the islands in the bog was sufficiently pressing for them to mount the enormous communal activity required for the task of stockpiling the timber and building the trackway, presumably when the waters were at their lowest after a dry period.

The work required for the construction of the track demonstrates that they had advanced woodworking skills and suggests some differentiation of occupation among the workers.

The length, straightness, and lack of forks or branches in the pegs suggest that they were taken from coppiced woodland.

Longitudinal log rails up to 20 ft long and 3.0 in in diameter, made of mostly hazel and alder, were laid down and held in place with the pegs, which were driven at an angle across the rails and into the peat base of the bog.

Notches were then cut into the planks to fit the pegs, and the planks were laid along the X shapes to form the walkway.

In some places, a second rail was placed on top of the first one to bring the plank above it level with the rest of the walkway.

Some of the planks were then stabilised with slender, vertical wooden pegs driven through holes cut near the end of the planks and into the peat, and sometimes the clay, beneath.

At the southern end of the construction smaller trees were used, and the planks split across the grain to utilise the full diameter of the trunk.

Sections of the track have been designated as a scheduled monument, meaning that it is a "nationally important" historic structure.

Other simpler tracks were made of dumps of brushwood laid along the line of the route and pegged in place by small stakes.

These were the most common form of trackway built to cross the bog.

In the later Bronze Age, between 1400BC and 800BC, the raised bog surface became much wetter, possibly as a result of climate change, and more substantial trackways had to be built.

The most impressive of these was the Meare Heath Track that was made from large oak planks laid on top of dumps of brushwood and transverse planks that operated like railway sleepers.

You can see a replica of the Sweet Track, walk along part of its route and imagine what the landscape would have looked like by visiting Shapwick Heath National Nature Reserve.

Someone who recently visited the nature reserves said: “We had a lovely walk through the Reserve and it was pleasant even on a dull day.

”We enjoyed walking along the Sweet Track - a replica wooden track built 6,000 years ago through the peat marshes. There were very few people around so it was a tranquil experience.”

Another person said: “Great place of peace and tranquillity, my wife stayed in the car and had a sleep whilst I walked around the marshes, this made it even more peaceful, would recommend.

”There's life everywhere, the hide's are in good condition, the paths very obvious. Like other's have said, being very flat makes it a lovely easy walk to take at a very leisurely pace.”

It’s a lovely place to explore.

A couple of years ago, The Sweet Track was added to Historic England’s ‘at risk’ register.

However, in 2022, it was removed following successful conservation work.

Julie Merrett from Natural England, said they were "very proud" of their work to protect habitat and history.

Historic England funded a research project into the track, which was found to be in "miraculously" good condition because it lies within waterlogged peat, where the lack of oxygen prevents decay.

Archaeologist Richard Brunning added: "It is heartening to have this example where the incredible preservation of this special site will be maintained for future generations."

If you enjoyed this blog post, please follow Exploring GB on Facebook for daily travel content and inspiration.

Don’t forget to check out our latest blog posts below!

Thank you for visiting Exploring GB.